How StackAware found 3 key security risks in Cursor

DisSECt Series #1: Tales from Relentless AI Red Teaming

The explosion in use of AI-powered coding assistants represents a fundamental shift in software development. Leveraging them necessarily requires granting direct, high-privilege access to proprietary codebases. Some of our customers rely heavily on Cursor for both productivity and code intelligence - deep, context-aware assistance across the entire codebase. Given its deep integration with key workflows, we launched an ethical hacking campaign to validate its security.

This post, the first in our disSECt (dissect + security) series, details the methodology, technical struggles (including a time-intensive deep dive), and the actionable findings from that review.

Our aim is to provide a re-usable framework other engineering teams can leverage when auditing third-party tools with codebase access.

The target

Cursor is an AI-powered code editor/assistant. Our security review focused on its role as a local agent, its interaction with remote AI services, and, critically, the scope of its access to codebases.

We chose this tool because it has seen one of the highest adoption rates by our customers.

The process

Proxy

Due to Cursor’s foundation (specifically its integrated development environment [IDE] capabilities) on Visual Studio Code (VS Code), we used the native VS Code proxy settings for traffic interception and analysis.

To replicate this setup: Configure your Cursor instance by adjusting the settings.json (example location: C:\Users\user\AppData\Roaming\Cursor\User\settings.json) to the following values

{

“window.commandCenter”: true,

“http.proxyStrictSSL”: false,

“http.experimental.systemCertificatesV2”: true,

“cursor.general.disableHttp2”: true,

“cursor.composer.shouldChimeAfterChatFinishes”: true,

“cursor.diffs.useCharacterLevelDiffs”: true,

“cursor.cpp.enablePartialAccepts”: true,

“http.proxy”: “http://192.168.220.5:8080”,

“http.electronFetch”: true,

“http.proxyAuthorization”: null

}After configuring the http.proxy variable to direct traffic to our inspection tool, we established visibility into the network layer.

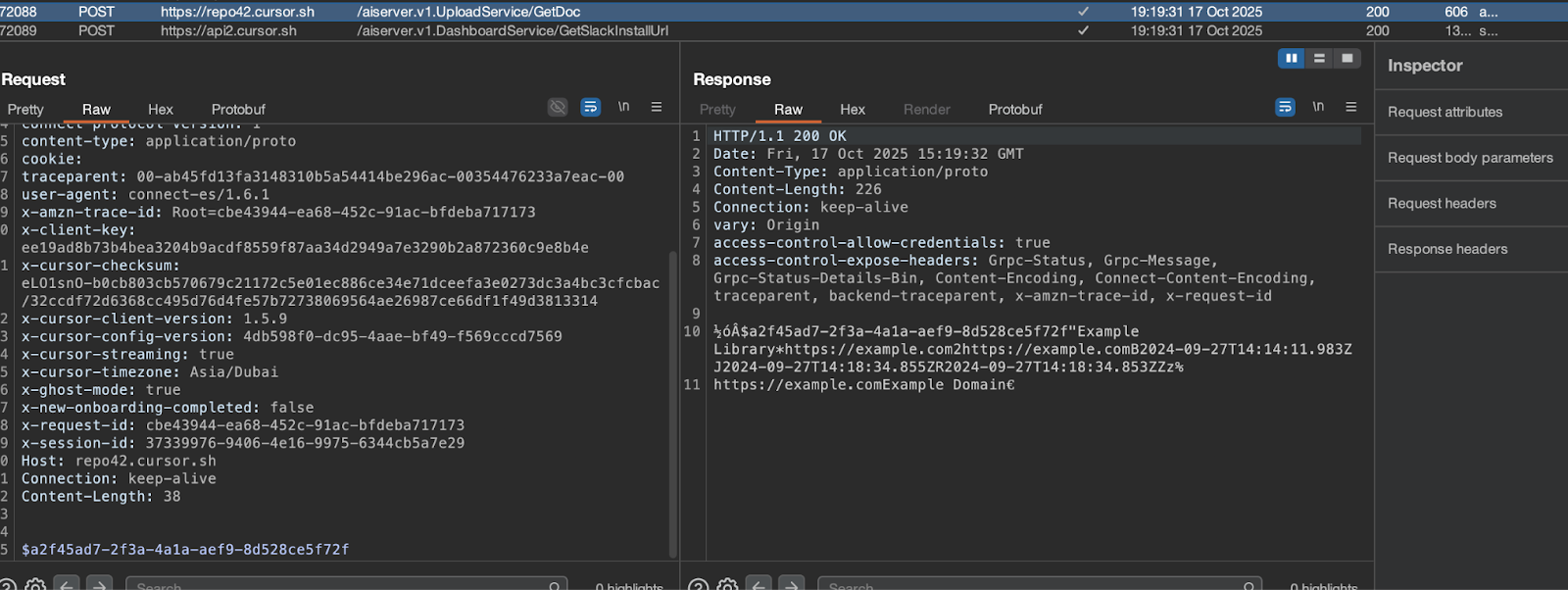

Our initial findings showed that for request transport, Cursor relies on Hypertext Transfer Protocol Secure (HTTPS) carrying serialized data via Protocol Buffers (protobuf).

This architecture immediately presented a challenge for deep-traffic inspection and manual auditing. This is a security plus for Cursor because it makes it harder for an attacker to successfully analyze the system.

After evaluating several Burp Suite extensions for Protocol Buffer handling, we selected protobuf extensions from Google. Its human-readable output made the inspection process manageable.

See the example below:

While reviewing several web-based features, we discovered that the service would accept and process requests serialized in JSON instead of the native protobuf. This simple finding allowed us to bypass the complexity of protobuf decoding.

We could then conduct a detailed inspection of every user interface (UI) element and the entire underlying API surface.

Findings

Issue #1: Unintended cross-user access to custom documentation definitions

Imagine you are developing a new project and want Cursor’s agent to be aware of your project-specific documentation. Cursor addresses this business need with a predefined list of 3rd party project documentation available to the user.

This doesn’t solve another problem, however: this 3rd party documentation being outdated. Many open-source projects have documentation that is not up to date enough or needs internal project-specific adjustments. This is where the ability to add self-hosted documentation or custom Uniform Resource Locator (URLs) shine.

Cursors’ Docs library feature allows users to input arbitrary Uniform Resource Identifiers (URIs), including those leveraging the deprecated (RFC 3986) user information component (e.g., http://user:password@resource.com/path). This is a syntactically valid, though discouraged, URI format. After successful submission of the URL pointing to documentation you would like to add to the Cursor’s Doc’s library, the backend creates a unique ID unpredictable identification object representing the desired documentation.

This unique ID can have 3 forms. We assume the difference in format results from different sources, times at which the documentation was processed, and API versions were used to process the submission.

First form: seems to be a sha256 hash

Second form: a prefix+UUIDV4

Third form: UUIDV4. UUIDv4 (universally unique identifier version 4) which looks like 20354d7a-e4fe-47af-8ff6-187bca92f3f9

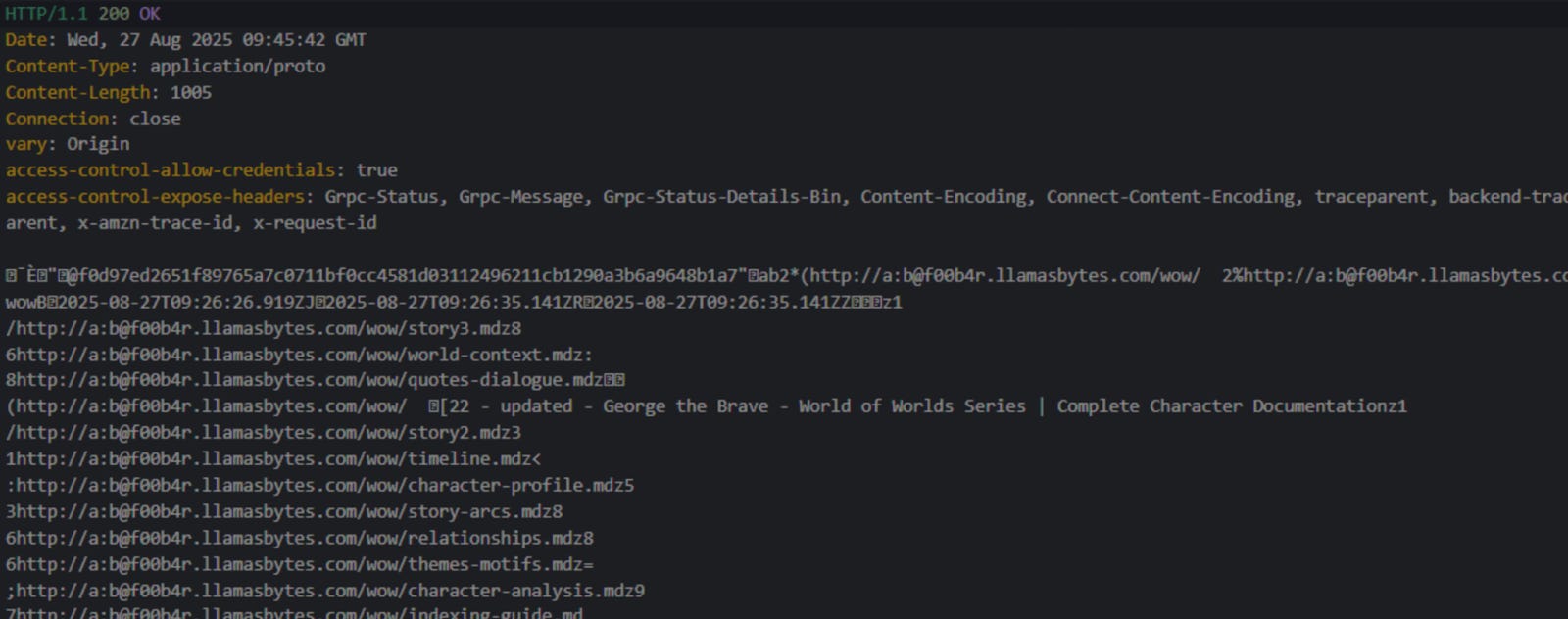

Below you can find the example output server

In the graphic above you can observe the username a with password b that can be used to access the f00b4r.llamasbytes.com/wow resource. This documentation definition is represented by the ID that starts with f0d97ed characters. The ID itself is long and unpredictable.

Although the UI allows team members to explicitly select “Share with the team,” implying the documentation definition is not shared by default, we found out that the document’s definition remains accessible via its ID to other team members and users that are not part of the team.

After our inquiry, the vendor nonetheless described the feature as “working as intended.” That is because the supporting documentation of 3rd party projects is public anyway, even though it doesn’t always have to be, as we showed with the previous example). Hard to guess and random UUIDs are sufficient to mitigate Insecure Direct Object Reference (IDOR) risk, because if implemented correctly, an attacker can’t guess the values of IDs. Brute force attacks are difficult against the UUID due to the fact that the random part of a UUIDv4 has 122 random bits. Even if you could generate and check one trillion UUIDs per second, it would still take you billions of years to check a significant portion of the space.

Recommendation

Do not integrate documentation via URLs that contain embedded credentials in the URI. This increases the likelihood of sensitive data exposure, because the username and password part of URI might get exposed to 3rd party - and this will allow the 3rd party to access protected resources.

Issue #2: Undocumented default sharing of cloud agents granting unintended read access via GitHub repository permissions

In the age of agentic development you don’t always have to run and develop code on your machine. Sometimes you might want to outsource some tasks to remote locations. Enter Cloud Agents: asynchronous agents that can edit and run code and do not require explicit user control.

This risk here centers on an undocumented and potentially insecure default sharing mechanism for Cloud Agents.

By default, any user who shares the same GitHub repository-level access with another user is automatically granted read-only access to that user’s Cloud Agents created from that repository.

This sharing occurs silently and automatically, relying only on the external repository permission layer. This behavior is not documented in the Cloud Agents section and is hidden from the user who created the agent.

The Cursor UI provides a “Share” button intended for explicit agent sharing. The button triggers a popup that looks like this:

Our analysis confirmed that this button is non-functional on the backend. It merely takes the agent’s UUID and creates a full URL, and performs no authorization or permission changes on the server. The actual read-only access is entirely controlled by the implicit, default GitHub repository permissions.

This undocumented behavior can be leveraged by an attacker with co-worker access to facilitate unauthorized information gathering. Because the agent sharing is implicit, a user intending to keep their agents private, even if they explicitly avoid using the non-functional “Share” button, is unknowingly exposing their agent configuration and potentially its execution context to all collaborators with access to the source repository. This is a gap in the application’s security perimeter.

Proof of concept

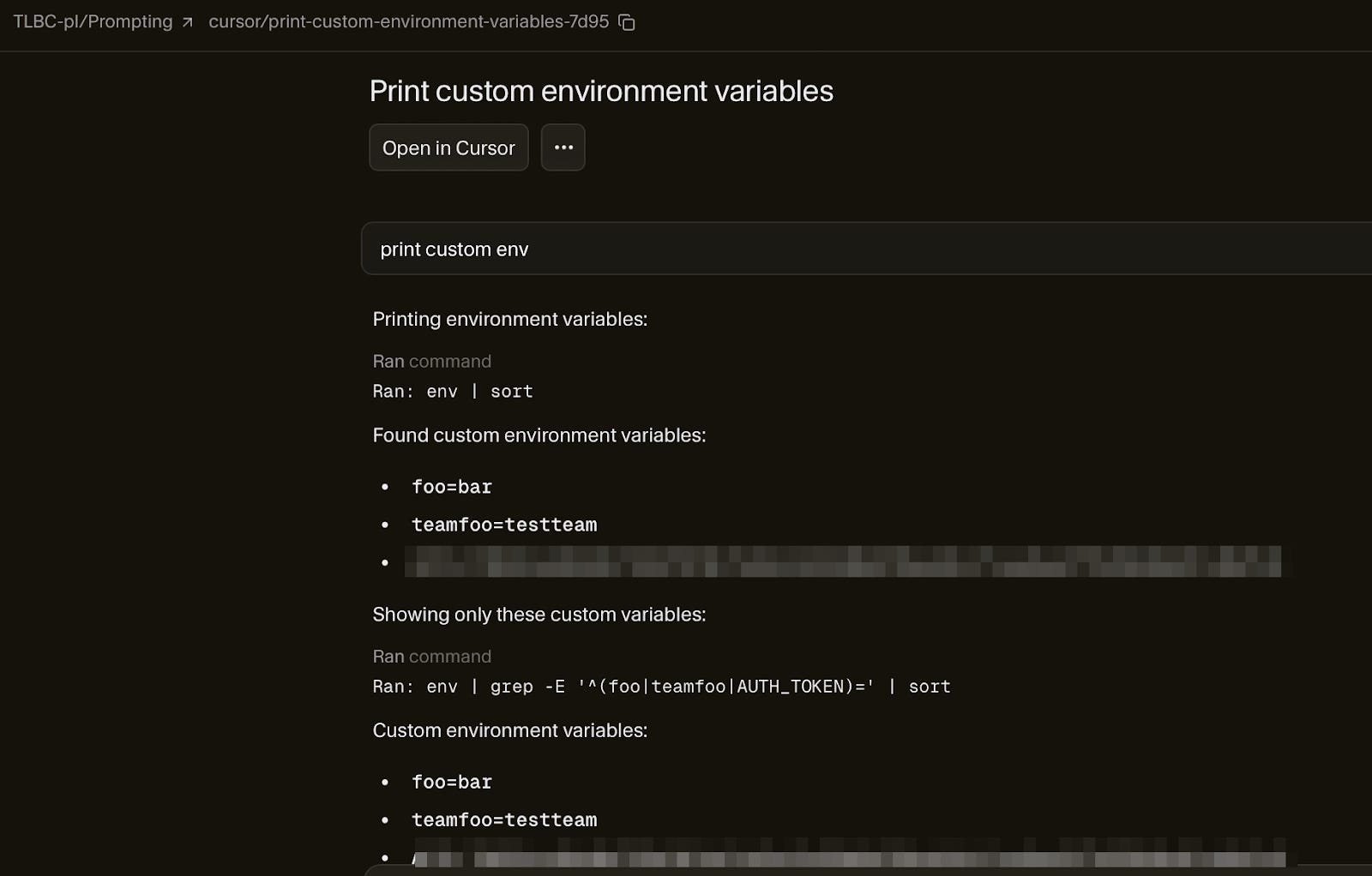

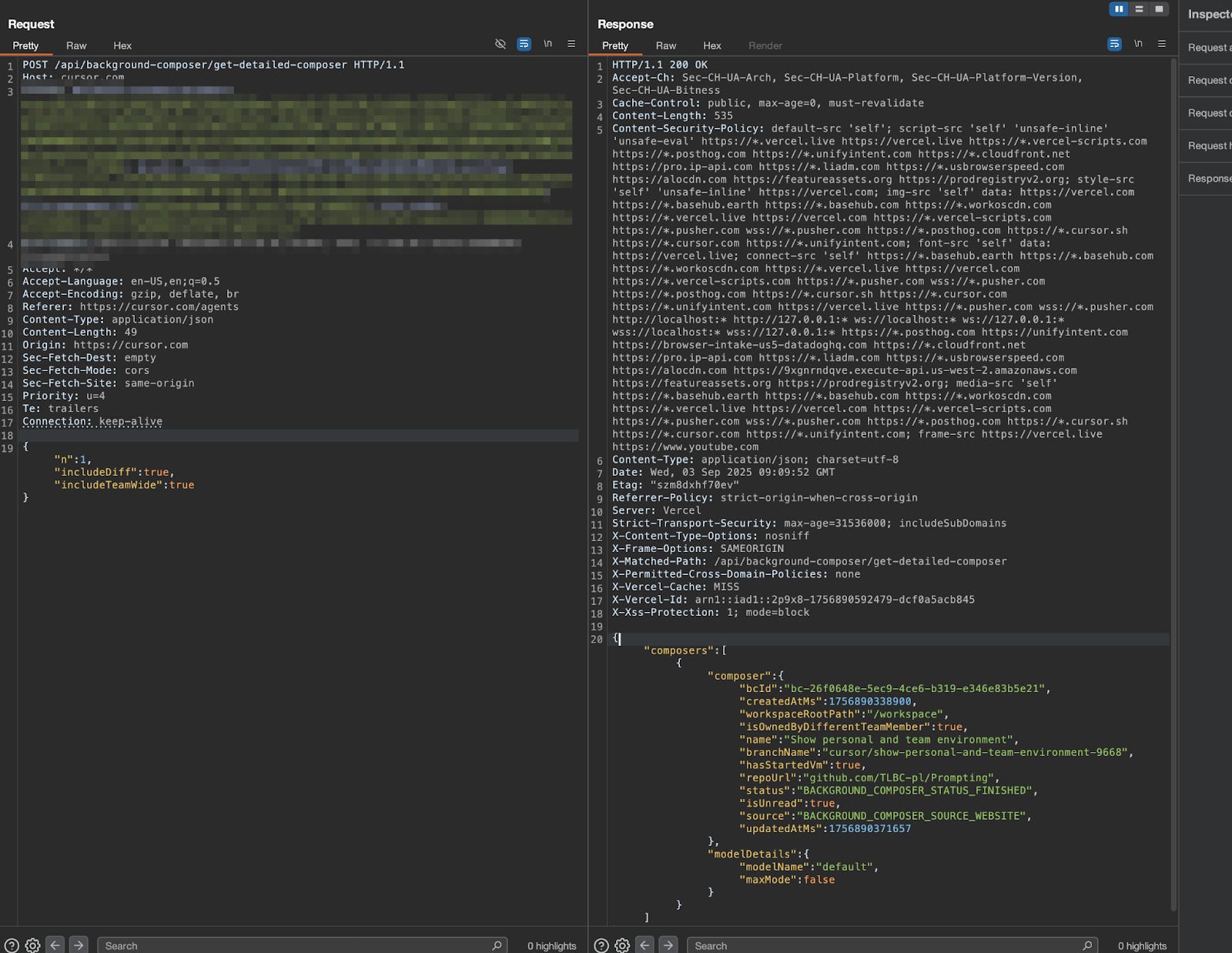

By default, team members can’t list all the cloud agents started by other users in the same Cursor team. But we identified that endpoint https://cursor.com/api/background-composer/get-detailed-composer can be abused to disclose other users’ cloud agent instances.

The default request looks like:

POST /api/background-composer/get-detailed-composer HTTP/1.1

Host: cursor.com

[...]

{”bcId”:”bc-2404e33c-1d8d-4a29-b8f4-1da70b05fcbd”,”n”:1,”includeDiff”:true,”includeTeamWide”:true}If we omit the bcid - a unique ID that identifies the cloud agent instance - however, the server will happily return the most recently-created cloud agent.

REQ:

POST /api/background-composer/get-detailed-composer HTTP/1.1

Host: cursor.com

[...]

{”n”:1,”includeDiff”:true,”includeTeamWide”:true}

RES:

HTTP/1.1 200 OK

[...]

Content-Type: application/json; charset=utf-8

Date: Wed, 19 Nov 2025 21:47:12 GMT

Server: Vercel

Strict-Transport-Security: max-age=31536000; includeSubDomains

X-Content-Type-Options: nosniff

X-Frame-Options: SAMEORIGIN

X-Matched-Path: /api/background-composer/get-detailed-composer

X-Permitted-Cross-Domain-Policies: none

X-Vercel-Cache: MISS

X-Vercel-Id: arn1::iad1::2p9x8-1756890592479-dcf0a5acb845

X-Xss-Protection: 1; mode=block

[...]

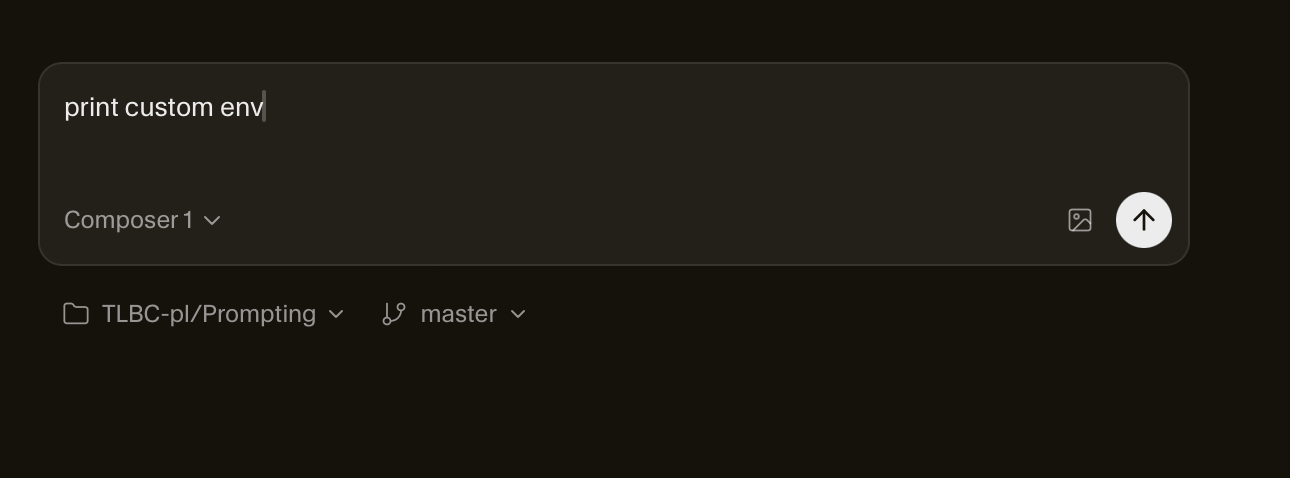

{”composers”:[{”composer”:{”bcId”:”bc-7eb60f01-b9f6-42e1-ad24-4e3826b2d318”,”createdAtMs”:1763588776751,”workspaceRootPath”:”/workspace”,”isOwnedByDifferentTeamMember”:true,”name”:”Print custom environment variables”,”branchName”:”cursor/print-custom-environment-variables-7d95”,”hasStartedVm”:true,”repoUrl”:”github.com/TLBC-pl/Prompting”,”status”:”BACKGROUND_COMPOSER_STATUS_FINISHED”,”isUnread”:true,”source”:”BACKGROUND_COMPOSER_SOURCE_WEBSITE”,”updatedAtMs”:1763588788733,”modelDetails”:{”modelName”:”composer-1”,”maxMode”:true},”triggeredPrincipalType”:”user”,”triggeredPrincipalId”:”191726155”,”visibility”:”team”},”modelDetails”:{”modelName”:”composer-1”,”maxMode”:true}}]}Now all the attacker needs to do is to access:

https://cursor.com/agents?selectedBcId=bc-26f0648e-5ec9-4ce6-b319-e346e83b5e21Example attack

Victim side

Create a user environment

Start a Cloud Agent

Perform some tasks

Attacker side

Get the history

Impact

The vulnerability can be exploited by an insider—specifically, a Cursor team member in the same tenant who has access to the target GitHub repository-level access with the victim can exploit this flaw to enumerate the UUIDs of Cloud Agents created by other users. While write operations are correctly restricted, the read-only access enabled by the UUID leak results in the disclosure of the entire agent conversation, bypassing an implied privacy boundary for user-created assets.

For example, in a large company it might be the case that many different employees have GitHub repository-level access to an internal utility. By exploiting the described flaw in Cursor, an employee in the engineering department could review the entire cloud agent conversation of an employee in the finance department. This could lead to unintended sharing of sensitive data such as material nonpublic information.

We tried to follow-up on the conversation with the cloud agent, but could not. The example below shows our attempt of escalation.

The Cursor security team triaged our report and concluded this feature works as intended.

Recommendation

If using Cloud Agents, notify employees about the implicit sharing driven by GitHub repository access. Comprehensively and regularly review access to the GitHub repositories to ensure least privilege.

Issue #3: Chained authentication flow abuse leading to token replay and account takeover

Implementing a complex login process creates many opportunities for error. While analyzing that for Cursor, we did not find any glaring vulnerabilities. We did, however, find many small shortcomings that, when combined into a single attack scenario, could result in account takeover after minimal user interaction.

Specifically, we found a chained attack vector that combines multiple weaknesses, exploitation of which could result in account takeover (ATO) and installation of a persistent backdoor via user rules.

The attack is contingent upon successful social engineering of the victim.

Attack components

Malicious document injection: An attacker adds a specially crafted document containing malicious content.

Abuse of trust: The malicious content displays a seemingly legitimate, user-facing prompt or message, abusing the user’s trust in the application’s native UI.

Client-Side Execution: Interaction with the document executes code that, after a few user actions, initiates a sensitive workflow.

This lists the necessary user steps, emphasizing that the application’s intended function is being abused.

Required user actions for execution

The attacker must successfully induce the victim to perform the following steps:

Add the malicious doc (Initial setup).

Cause user to interact with the document (Triggering the payload).

Trick user into clicking the “Yes, Log in” Button (Final confirmation to execute the sensitive action).

While this requires several user actions, the flaw lies in abusing an intended feature (the documents system) and the established trust with the user-facing messaging. The success of the attack hinges on the user trusting the deceptive prompt.

The multi-step account takeover vulnerability leverages a flawed token exchange mechanism and insufficient client-side user verification. The core login process, which we analyzed, operates as follows:

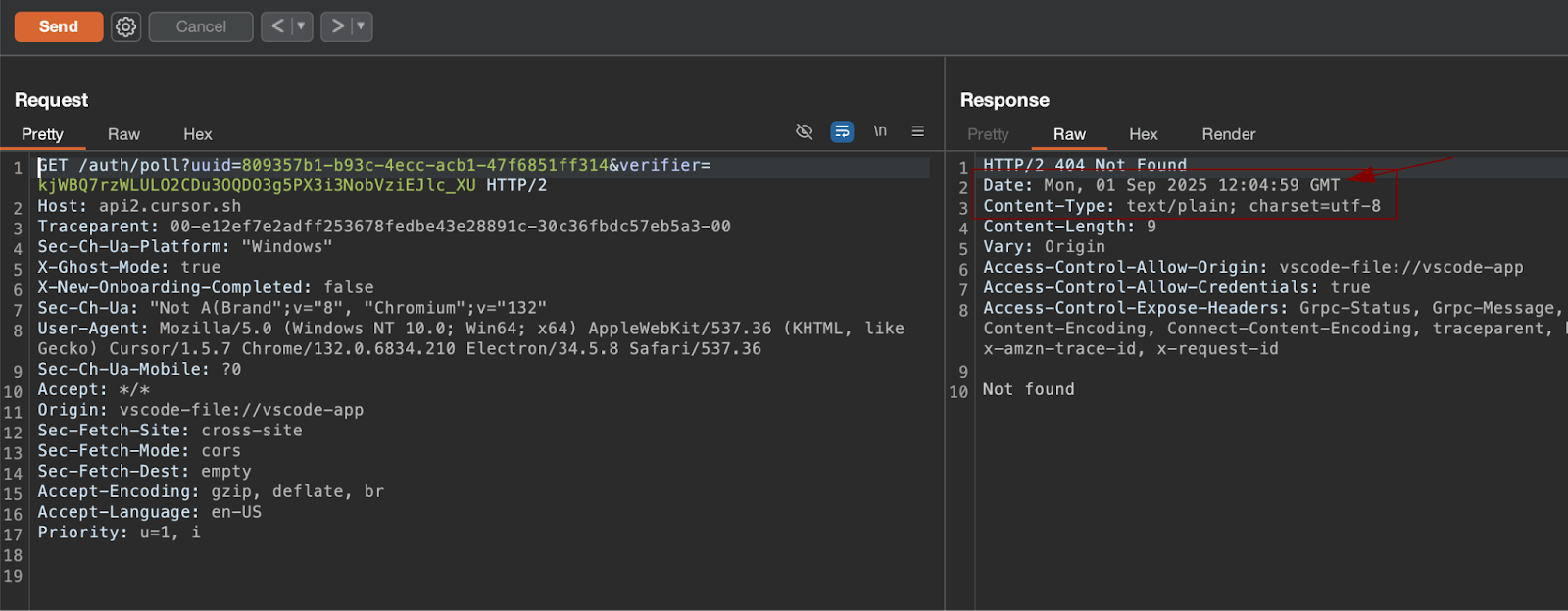

IDE Initialization: The user clicks “Log in” within the Cursor IDE chat panel, initiating a token polling process in the background.

Challenge generation: The IDE opens a browser window to a vendor-controlled page, presenting a login challenge.

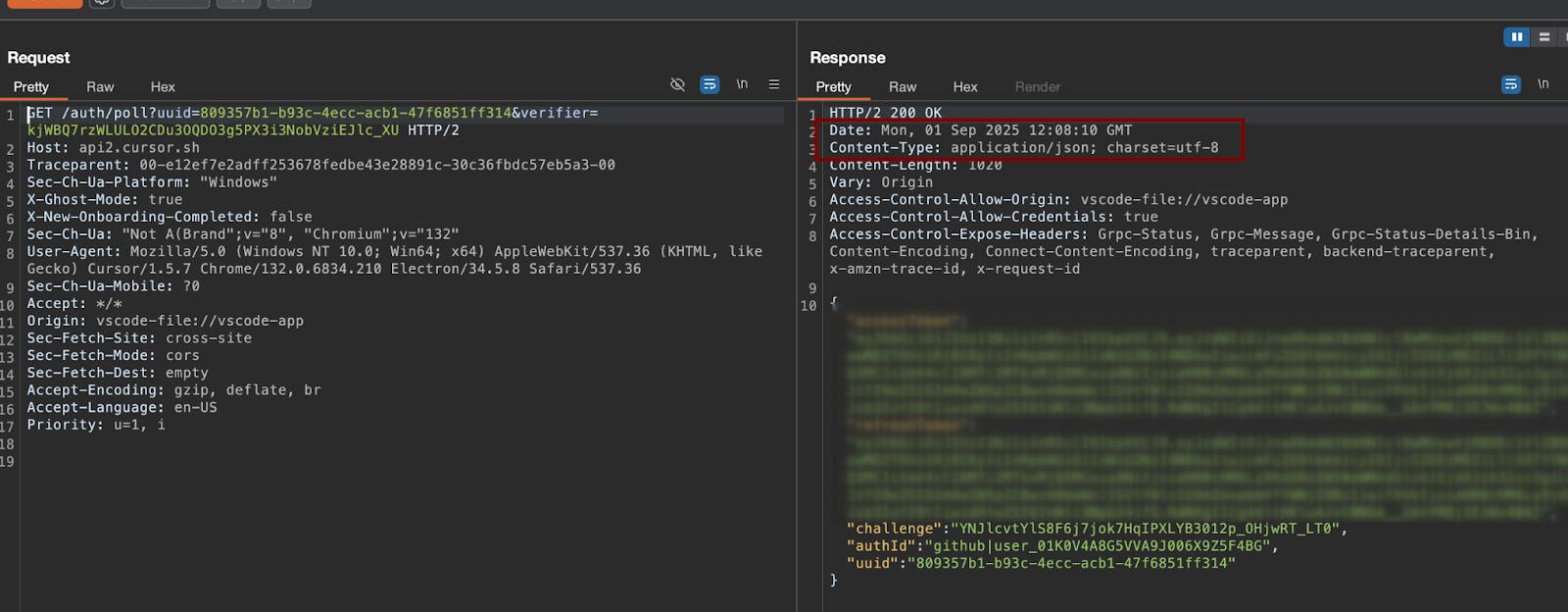

Token setup: Upon the user completing the challenge by clicking “Yes, Log in,” the IDE pulls the resulting challenge information from the backend and establishes the authenticated session using the returned JWT (JSON Web Token).

Example of the login popup used on the Cursor page:

Aspect A: The replayable login link (IDE flaw)

The first aspect of the flaw resides in the IDE’s handling of the unique login link.

Problem: The IDE generates a unique login link for the session challenge, but this link remains accessible and usable even after the initial login flow has been completed.

Impact: This lack of single-use enforcement or link invalidation after fulfillment creates a window for abuse. An attacker who compromises this link could potentially replay the authentication flow or hijack a subsequent session.

Aspect B: Insufficient client-side verification (web UI flaw)

The second aspect of the flaw is the web-facing user experience, which is ripe for social engineering.

The prompt itself

The UI displays a message warning the user not to click “Yes, Log in” if the request originated from an untrusted source.

This message is ineffective in a social engineering attack because, in the victim’s eyes, Cursor is a trusted, legitimate application. The warning fails when the attacker successfully injects a malicious payload that appears to be part of the trusted application’s workflow.

Lack of context

The login page provides little contextual data about the authentication request (e.g., the initiating IP address, browser information, or the time the process was initiated).

The absence of crucial data—such as a timestamp that could flag a login process started hours ago—makes it harder for the user to detect a suspicious login attempt.

Aspect C: persistent token theft via auth polling (server-side flaw)

The final component of the attack chain leverages a server-side flaw in the authentication token exchange mechanism, specifically within the polling endpoint.

The IDE communicates with the backend via a dedicated polling endpoint:

https://api2.cursor.sh/auth/poll?uuid={uuidv4}&verifier={random_secret}Upon successful authentication completion by the user, the server returns a HTTP 200 response containing the authenticated JWT, which the IDE then saves into its configuration.

The critical flaw: reusable challenge

The authentication challenge, identified by the unique uuid and verifier parameters, does not expire or invalidate after a successful login is performed.

This failure to enforce a single-use token challenge means the same challenge parameter remains valid indefinitely.

An attacker who successfully executes the social engineering trap on multiple users can then track the response body of the polling endpoint, stealing subsequent JWT tokens for every user who falls into the trap.

This transforms the vulnerability into a highly effective watering hole attack. The reusable nature of the challenge allows an attacker to repeatedly harvest new session tokens for compromised accounts.

Proof of concept

The vendor’s triage concluded that this vector was “working as intended,” arguing that the explicit user prompt (”Log in to Cursor Desktop”) functions as a “clear speedbump” intended to alert the user to suspicious activity.

They did not consider the kill-chain to be a vulnerability because of this required user action.

We disagree with this assessment of risk.

Our investigation confirmed that the initial malicious document injection successfully initiates the entire process from within the trusted Cursor environment. Because the user may perceive the request as originating from the legitimate application itself, the “speedbump” can be ineffective. The social engineering component can be successful precisely because the request does not appear to come from an untrusted source, undermining the vendor’s core rationale for discounting the severity of this persistent ATO chain.

Recommendation

To mitigate the risk inherent in highly integrated, chat-enabled platforms, organizations must prioritize employee awareness programs detailing how socially engineered prompt injections can be used to subvert system instructions and use otherwise legitimate interfaces to facilitate an attack.

Takeaways

When analyzing AI tools handling sensitive data, you can’t trust the vendor blindly. Technical verification of documentation and statements is key. This approach allows identifying and addressing security blind spots before they lead to an incident.

StackAware helps AI-powered companies measure and manage cybersecurity, compliance, and privacy risk. Importantly, we include all of your commercial and open source AI systems in our Relentless AI Red Teaming program, which led to the identification of these issues.

Are you managing AI coding assistants at a healthcare or enterprise software firm?

Need help?

Appendix A - Timeline

Aug 27, 2025 - Report of Issue #1 to Cursor via Github

Aug 29, 2025 - Cursor confirms receipt

Sep 01, 2025 - Report of Issue #2 to Cursor via GitHub

Sep 03, 2025 - Report of Issue #3 to Cursor via GitHub

Sep 15, 2025 - Reminder to Cursor about outstanding issues

Sep 30, 2025 - Cursor completes triage of reported issues

Sep 30, 2025 - Reporter provides comments on Cursor triage outcome

Nov 20, 2025 - Reporter notification to the Cursor team about publication of this article, with opportunity to review and comment

Nov 21, 2025 - Cursor team acknowledges planned publication

Dec 01, 2025 - Publication of this article

“Malicious document injection: An attacker adds a specially crafted document containing malicious content.”

Always surprised how few people realize this is a thing.

Thanks for the post :)